Your midweek-break. (On mastering anything. )

Five things that might just make your day, by Schalk Holloway.

Hello, one and all!

Welcome to another edition of Guns, God and Speculative Fiction. Sincerely hope you find something just for you in this week’s selection. 😊

Much love, Schalk.

Quick navigation:

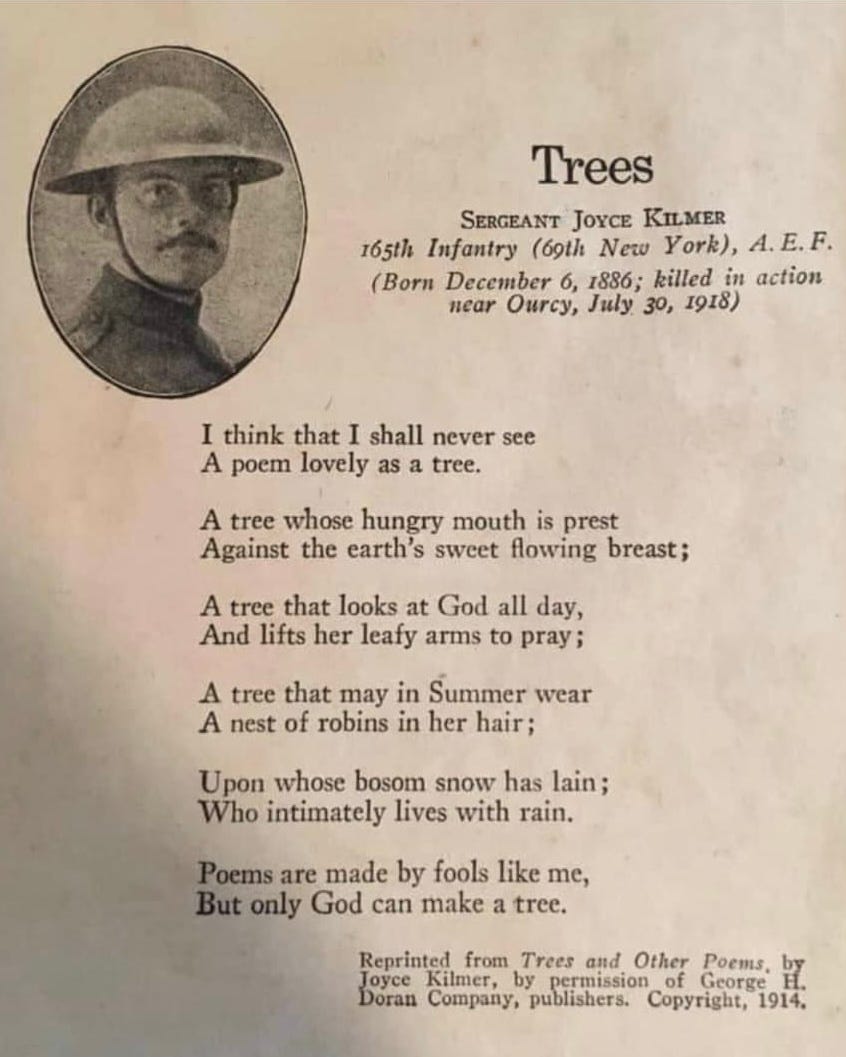

Something that inspired me.

Sometimes when you click on the image above, it’ll take you to some goodies. 😉

Musings on an important topic.

On mastering anything.

So far, this year, I’ve had at least two major wobbles in my writing.

They were good wobbles though, and like with any good wobble they came with momentary angst, a sense of danger, the fear of falling.

They let me know I’m not there yet, that I’ve yet to master my craft. At any stage I could fall off!

Okay, that sounds overly dramatic. Lol. But it’s also how I felt during both wobbles. And I remember it vividly now! Looking at my MacBook over my shoulder. Daring it to taunt me again. Daring it to take aim at my inadequacy again. Willing it to heed the warning in my eyes lest I smash it through a w—

Anyway. Cough. Back to the topic at hand.

The wobbles themselves were easy to understand, easy to see for what they were: both came with the realisation of how much I still have to learn. To a dear friend, I found myself saying, ‘I feel like a draughtsman in the world of architects, like a McDonald’s grill man in a world of Michelin Star Chefs, like a touch rugby player running out to a World Cup match.’

It’s not imposter syndrome. It’s simply an awareness that I’ve yet much to learn.

In many ways, I’m always aware of how far I still have to go.

Even when I’ve come far in anything, I’m at the same time fully confident in my abilities and fully aware that the bar can be set ever higher.

So what to do, what to do, when the feeling comes?

You should’ve guessed it by now: I always find myself gravitating back to the fundamentals.

I’m always asking the question: do I truly understand the fundamentals and which of them do I still need to master?

Each and every activity, sport, craft and art that I’ve ever attempted came with fundamentals. Public speaking? Fundamentals. Relationships? Fundamentals. Micro navigation? Fundamentals. Strongman? Fundamentals. Hermeneutics? Fundamentals. Combatives or martial arts? Fundamentals. Shooting? Fundamentals. Drawing? Fundamentals. Sales? Fundamentals. Systems? Fundamentals. Chillies? Fermentation? Sauce making? Fundamentals. Fundamentals. Fundamentals. Classical guitar? Fundamentals.

Writing? Yup. Fundamentals.

To date, my approach to life, and truly also my saving grace, has always been my tendency to consider and master the fundamentals of whatever it is that I am attempting.

What are the fundamentals involved in this or this or that?

How would I even identify the fundamentals in this or this or that?

Who might help me understand the fundamentals in this or this or that?

What work do I need to put in should wish to master the fundamentals of this or this or that?

Am I willing to put in that work?

So here I find myself two years into my full time writing career, fourth novel (and tenth book) almost complete, and I’m still working on my fundamentals. Because, you know why?

I’m simply not there yet.

And that’s okay because I know myself, I trust myself, and I’m putting in the work. Each and every day.

“THE Oxford Dictionary defines the word Fundamental (usually Fundamentals) as “a central or primary rule or principle on which something is based.” Fundamentals are primary in the sense that they are what is most, or of first, importance. Fundamentals are those principles on which everything else is built—they are the principles that lie underneath everything else that we do. As such, whatever the Fundamental leads to is of secondary importance; if the Fundamental is not executed correctly then whatever else the Fundamental is a part of will not be executed correctly either.”

Excerpt From Schalk's Little Book on Fundamentals

A track I’ve got on repeat.

Poetry.

The Gift of Walking

Never a gift, as good as thee,

has set me off, has set me free.

Oh walking, wise, beyond our years,

your knowledge sings, into our ears.

Oh walking, calm, so full of peace,

our hearts you set’ll, when in you reach.

Oh walking, subtle, shining gems,

when beauty comes, with nature’s hem.

Oh walking, dear, you are to me,

A gift so small, a gift so free.

And may my prayer, be heard this day,

may never walking, go far ‘stray.

#mixedrhyme Six Duets, 8 Syllables, AA BB CC DD EE (Iambic Meter)

© Schalk Willem Holloway

An excerpt from a book.

Excerpt from ‘Little Book on Fundamentals

GRAVITY’S direction of force is always downward (or towards the center of the earth).

All objects of mass have an imaginary (or hypothetical) position at which the combined mass of the object appears to be concentrated. Flowing from this position, they then have what could be called a line of gravity. Imagine for a moment a line, with an arrowhead attached to the bottom, being hung from this hypothetical position. This line and arrow, when stationary, will be pointing towards the center of the earth. This imaginary line is what we call the line of gravity.

It’s also important to note that this hypothetical position, the center of gravity, does not necessarily have to lie within the object. The dimensions and distribution of the object’s mass will determine where this point lies. However, due to the anatomical dimensions of the human body we can approximate a center of gravity for humans. This position, what we refer to as the COG, usually lies to the front of the second sacral vertebra. When facing the front of the human body we can imagine it to be an inch or two below the navel. If we had to draw a line from the second sacral vertebra to this front and below naval position, the COG would usually lie somewhere towards the middle on this line on what certain people refer to as the body's vertical axis. In general, there is some variation between male and female due to differences in hip dimensions; specifically each and every human will have slight differences in this position due to variations in body shape, size and proportions.

Back to the imaginary line of gravity. This line and arrow, when stationary, will also be pointing to the middle of the base as it’s the base that is bearing the weight of the mass.

Notice these four principles of stability:

When the base is large, the object is said to be more stable as the line of gravity needs to move further for it to fall outside the base. As example consider a person down on all fours, weight evenly distributed between both hands, knees and feet. It will be quite difficult to cause them to lose balance. When the base is small, stability will decrease as it becomes easier for the line of gravity to move outside the base. Here we can imagine a ballet dancer, feet together, raised on her toes. Should we trap her feet it wouldn’t take much force to push her off balance.

When the base is wide on one axis but narrow on the other, stability will increase in the wide direction of the base but decrease in the narrow direction of the base. Imagine the traditional martial artist in a deep horse stance. They would be able to manage a lot of incoming force on the line stretching form ankle to ankle, give them a firm punch on the chest however and they will easily lose balance towards the rear. This principle also relates to stance integrity which will be discussed in more detail in the next chapter.

As the COG lowers, stability increases because it becomes less and less likely for the line of gravity to fall outside the base. Imagine the increase in stability from a person standing, to kneeling, to all quadruped (all fours), to lying flat on their belly or backs.

Influencing the stability and the balance of a human being is nothing more than influencing the relation of the line of gravity to their base. However, as we don’t necessarily want to take the time to work out the exact location of the line of gravity we use the hypothetical COG mentioned above as easy reference.

To destabilise and unbalance a human being then is to move their COG outside of their base. When you understand this principle you understand two things: one, that all takedowns are essentially doing the same thing (moving the COG outside of the base); two, that you don’t need to know any specific takedown technique to actually facilitate a takedown; improvisation becomes quick and easy. We’ll cover this in more detail in a later chapter.

5.0 out of 5 stars Concise, insightful

Reviewed in the United States on June 16, 2021

This will be a short read with long lasting benefits. The information is both detailed and practical, with excellent presentation.

The title might be misleading, though. While the beginners will benefit greatly from reading the book, I feel it is the instructors who will reap greatest rewards. Even if you have a good feel for and command of your tecnical arsenal, you will now really UNDERSTAND the immutable laws of physics underneath it, which will make teaching easier and more enjoyable for both the instructor and the students.

I am eagerly awaiting for the next book in the series.